Our story

Dutti’s biggest setbacks

The Migros founder was renowned for taking risks and trying new things out. Four examples.

navigation

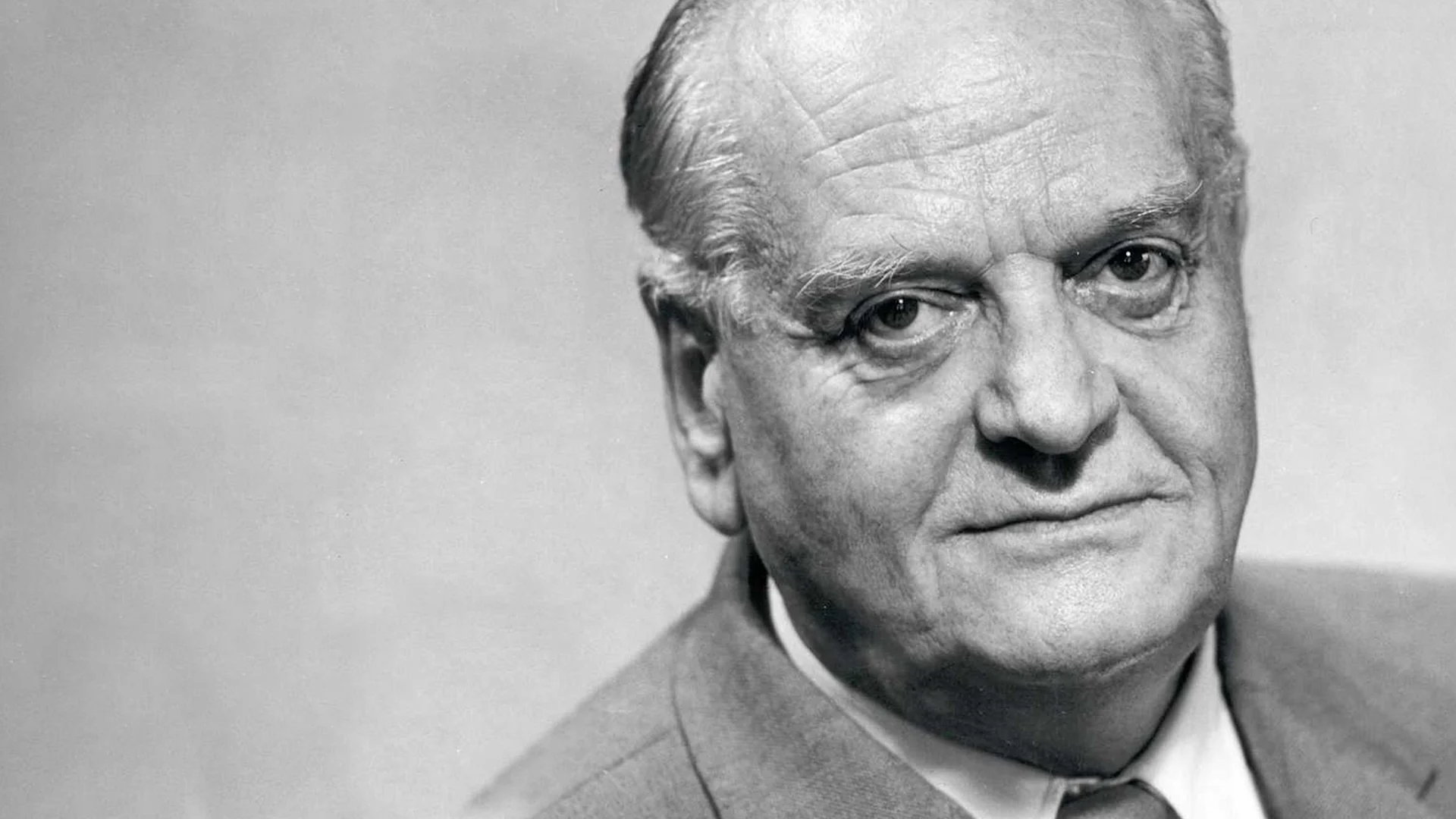

Gottlieb Duttweiler

The Migros founder did more than just reinvent shopping. He was a reluctant politician, a courageous lateral thinker and a charming yet fiery character. He was loved and hated in equal measure.

“Dutti der Riese” is a 2007 documentary by Martin Witz, portraying Migros founder Gottlieb Duttweiler.

Gottlieb Duttweiler (born in Zurich on 15 August 1888) grew up with four sisters. His father, a former innkeeper, worked as an administrator at the Zurich Food Association. This female-dominated household left its mark on Dutti: throughout his life, he lent a sympathetic ear to women and often sought their advice. He was also regarded as a great charmer, who later enthralled customers at shop openings as head of Migros. Contemporaries also described Dutti as a “fisher of men” – a person who was able to convince more than just women of his ideas.

Dutti’s talent for business began to shine through at school: he earned money by breeding rabbits, guinea pigs and white mice as well as by taking portrait photos. He dropped out of secondary school, instead opting for an apprenticeship at food wholesaler Pfister & Sigg, where he later became a partner.

In 1911, Duttweiler met Adele Bertschi on a train and fell head over heels in love with the 18-year-old. “I saw a girl today and I want her to be my wife,” he told his mother. While she was initially reticent, he pulled out all the stops to woo her. The couple married in 1913 and stayed together for the rest of their lives, going through thick and thin together. After Duttweiler’s death in 1962, his wife took over as the guardian of the 15 Migros theses they had written together over almost three decades.

A highly talented food wholesaler with a strong international network, Dutti earned a lot of money in just a few years. He lived the high life, filling his home in Rüschlikon on Lake Zurich with fine art and antique furniture. However, after the First World War, food prices plummeted and Dutti suddenly lost his entire fortune. He tried his hand at managing a coffee plantation in Brazil, but this new venture failed.

Duttweiler’s big success came in 1925: he founded Migros with the idea of selling products at unrivalled prices by buying directly from wholesalers and cutting out the middleman. A fleet of sales vans was assembled in Zurich.

At this time, Dutti put all his eggs in one basket – winning the favour of housewives. A flyer showing the timetable of the mobile shops began with the words: “To the intelligent housewife who can do the maths”. Years later, Duttweiler said the following at a convention in Boston: “(...) I am happy to admit that I was only able to revolutionise the food sector because I found an intelligent partner – the Swiss housewife.”

Duttweiler’s Migros expanded rapidly, with sales vans and bricks-and-mortar shops appearing in more and more cantons. The established retail sector put up fierce resistance to price cutter Dutti, and various food manufacturers boycotted Migros at the time.

Dutti always responded to such blockades with clever moves that made his company even bigger and stronger. For example, he founded his own food production enterprise. He laid the foundations for this step in 1928 with the acquisition of Alkoholfreie Weine & Konservenfabrik AG in Meilen (Canton of Zurich).

In 1933, Migros’ competitors, namely small and medium-sized retailers, succeeded in getting the federal government to issue what was known as the “branch store ban”. It remained in force until 1945 and imposed restrictions on Dutti’s company, preventing it from opening new shops. To fight the ban more effectively, Duttweiler entered politics – reluctantly and to protect his interests. He founded the “Landesring der Unabhängigen” (“Alliance of Independents”) party and was elected to the National Council in 1935. He sat as a member of parliament for 24 years in total.

Dutti was an eager go-getter who repeatedly upset the sedate Bernese political scene. He fought vigorously for freedom of trade and against cartels, but was met with fierce resistance. He was often accused of only entering politics out of self-interest and for the benefit of Migros.

In the 1910s, Duttweiler was still a conventional food wholesaler. As the head of Migros, he increasingly challenged conventional capitalism. He eloquently set out a vision of a new market economy that focused on people and not profit.

Dutti followed up on his big words with equally impressive deeds: in 1940, he announced the transformation of Migros into a cooperative – thereby giving away his life’s work to the Swiss people.

In 1948, he founded the Migros Club School, which made education affordable, even for the poorer classes.

In 1957, Dutti created the Migros Culture Percentage, whose funding is directly linked to sales. Thanks to this organisation, Migros now spends around CHF 121 million a year on the public good – for example on culture, education and leisure activities.

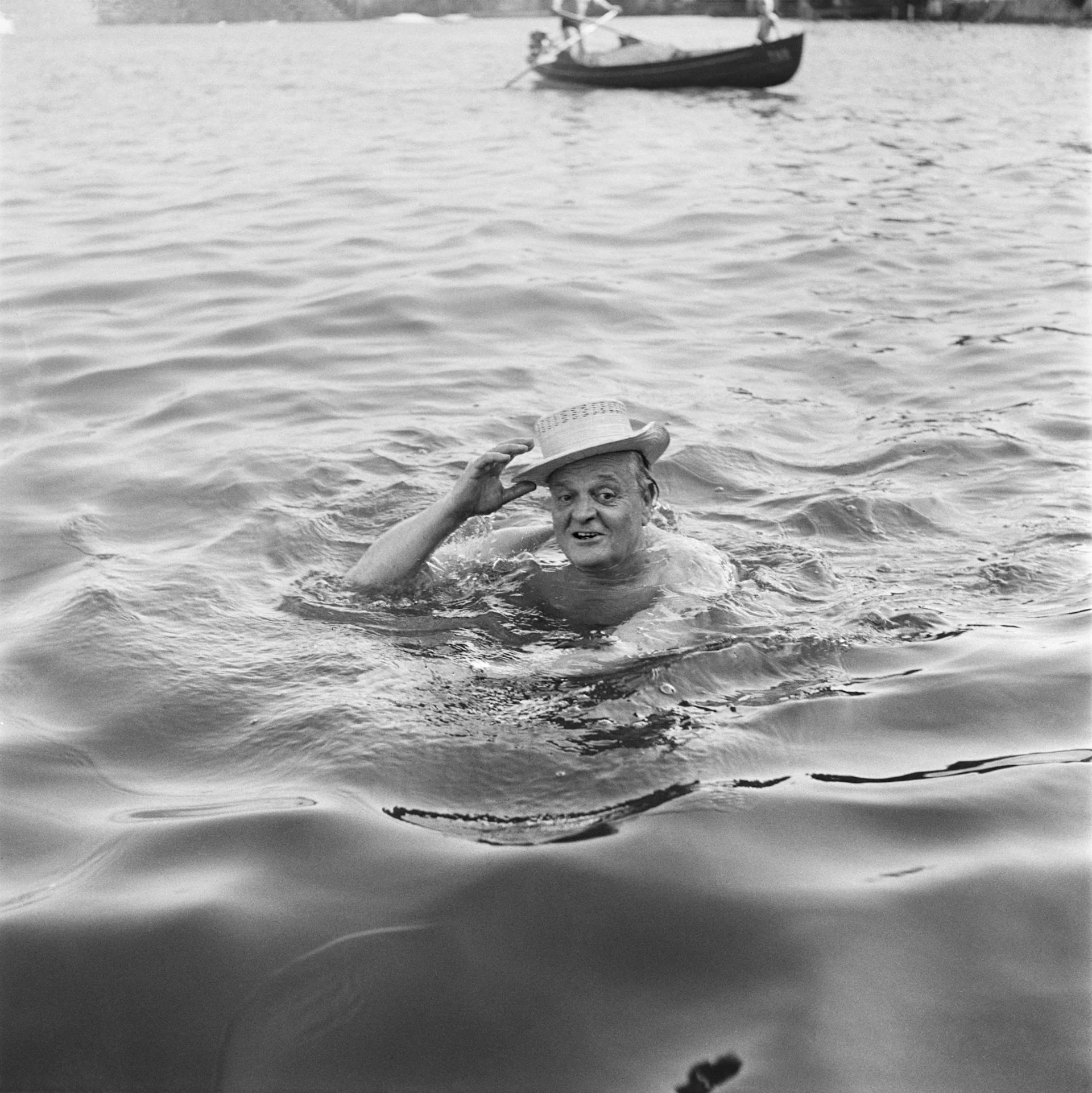

Migros shaped the consumer culture of Switzerland's booming economic miracle: Duttweiler opened ever larger and more attractive supermarkets with an ever wider range of products. During the lean wartime years, shopping had been a mere necessity, now it became an experience. When a new Migros store opened its doors, it often turned into a mass event – something akin to a public festival.

Whether it was ice cream, vinyl records, vacuum cleaners or fridges, Migros made many things available to the general public that were cutting-edge and in high demand at the time. All of these things were always cheaper in Duttweiler’s supermarkets than in specialist shops.

Towards the end of Duttweiler’s life, hostility towards him abated and the conservative press now also paid him respect. The general consensus was that he had done a great deal for Switzerland and especially for the poorer people in the country.

When he died on 8 June 1962, there was an enormous outpouring of sympathy. The funeral was held at Zurich’s Fraumünster church, but there was not enough room for the vast number of mourners. The mass service was broadcast to three other churches. The “Blick” newspaper paid tribute to Dutti: “A great philanthropist has died. We have lost a man who never became a Federal Councillor, but who turned Switzerland upside down in so many ways that few people could keep up. A great heart has stopped beating.”

Find out more about the early sales vehicles, the first self-service shop and founder Gottlieb Duttweiler and his wife Adele.