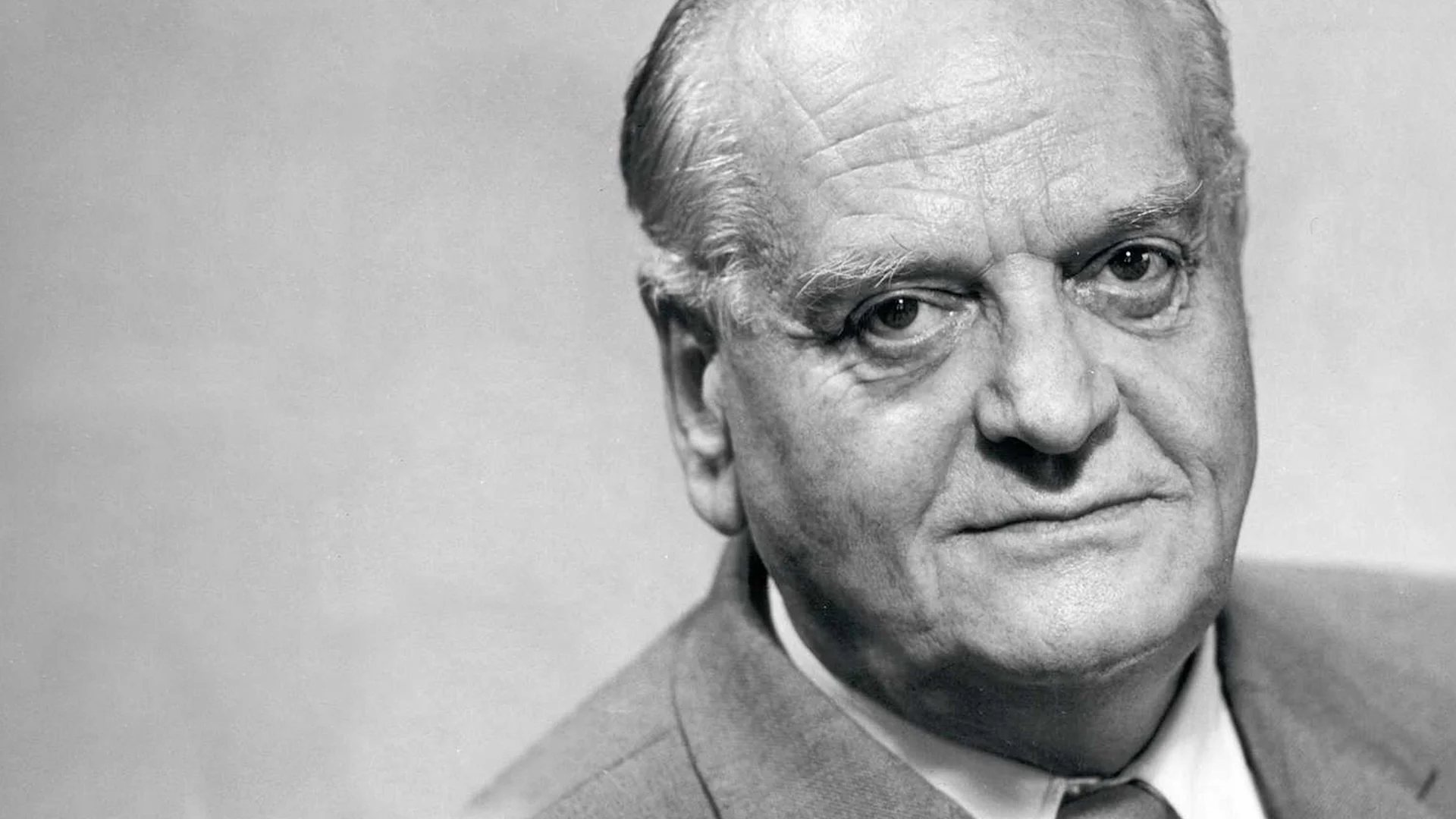

Gottlieb Duttweiler

The Migros founder was a visionary, lateral thinker and charming yet fiery character – and he did more than just reinvent shopping.

navigation

Our story

Some contemporaries considered the founder of Migros eccentric. Others revered him like a saint. This is borne out by newspaper reports of the time. Why did Duttweiler trigger such strong emotions in people?

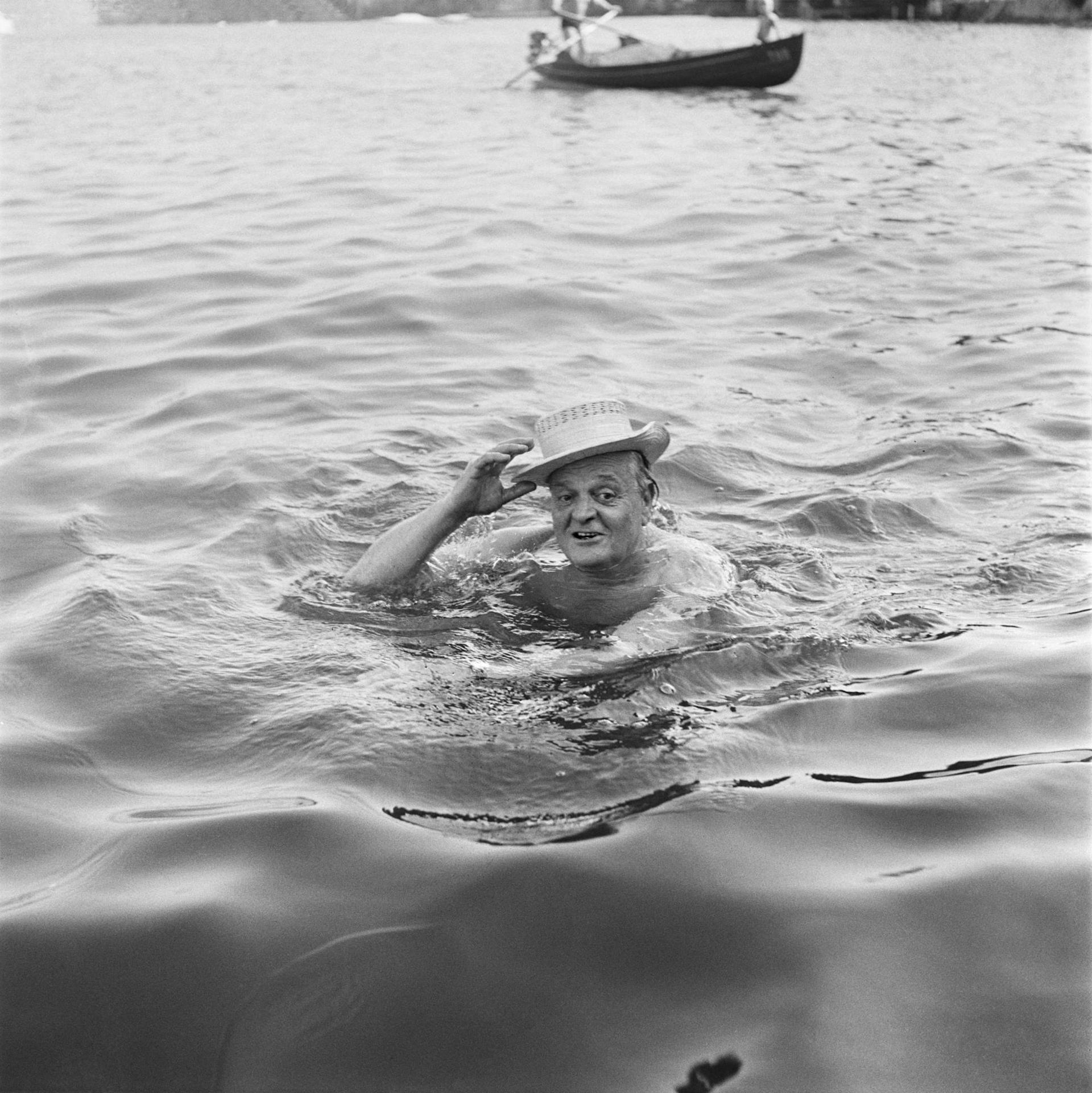

Gottlieb Duttweiler grew up in Zurich in a family where women very much ruled the roost. He was the only boy among five siblings. His father, a former innkeeper, worked as an administrator at the Zurich Food Association. Some biographers are convinced that this female-dominated household had a strong influence on Dutti. Throughout his lifetime, he was always willing to listen to ideas from women. His wife Adele was his closest confidante. He called Elsa Gasser - his advisor and a brilliant economist and former NZZ journalist - "my firm salaried opponent" because he appreciated the fact that she challenged him as well as her bold ideas. Gottlieb Duttweiler was also seen as a great charmer, who would enchant customers at shop openings in his role as Migros boss. Contemporaries also described him as a "fisher of men" who could sell his ideas to everyone – male and female alike.

When Duttweiler founded Migros in 1925, he gambled everything on one goal: winning over housewives. He had five sales vans drive around Zurich, offering products at unbeatable prices. A Migros flyer at the time began with the words "To the housewife who has to make everything add up". The company founder was certain that women would appreciate the benefits of his mobile shops.

I'm happy to admit that I was only able to revolutionise food retail because I found an intelligent partner: the Swiss housewife.

Even as a boy, Duttweiler annoyed his teachers with his restless, rebellious nature and endless refusal to accept the status quo. At the behest of his school's directors, he dropped out of cantonal school and completed a commercial apprenticeship instead. Even as a child, he had enjoyed trading, for example in home-bred guinea pigs. When he founded Migros, in 1925, he revolutionised traditional Swiss retail.

He was like an elephant stepping onto the finely spun web of price fixing, producer trusts and politicians (...).

Dutti continued trying out new business ideas throughout his life, always taking any setbacks on the chin. Migros owes its foundation to a catalogue of major fiascos in Duttweiler's life, including as a sugar-cane producer in Brazil. But he never let this stop him, and always sensed the next opportunity. One prime example of this was his attempt to shake up the taxi industry. In 1951, he bought 100 small taxis in London, which he then used to transport passengers in Zurich at low cost. He wanted to make taking a taxi affordable to office workers. The move resulted in a price war, which Dutti unfortunately lost. Although he was forced to sell his cars, he claimed a victory because taxi fares fell permanently as a result.

Migros President Gottlieb Duttweiler wanted to cause upheaval in the Zurich taxi industry. His threat to flood Zurich's streets with 100 yellow cabs quickly united Zurich's taxi operators.

In 1933, Migros' competitors, namely small and medium-sized retailers, succeeded in having the Federal Government impose a 'branch store ban'. This remained in force until 1945 and hampered Dutti's company, which was no longer permitted to open new shops.

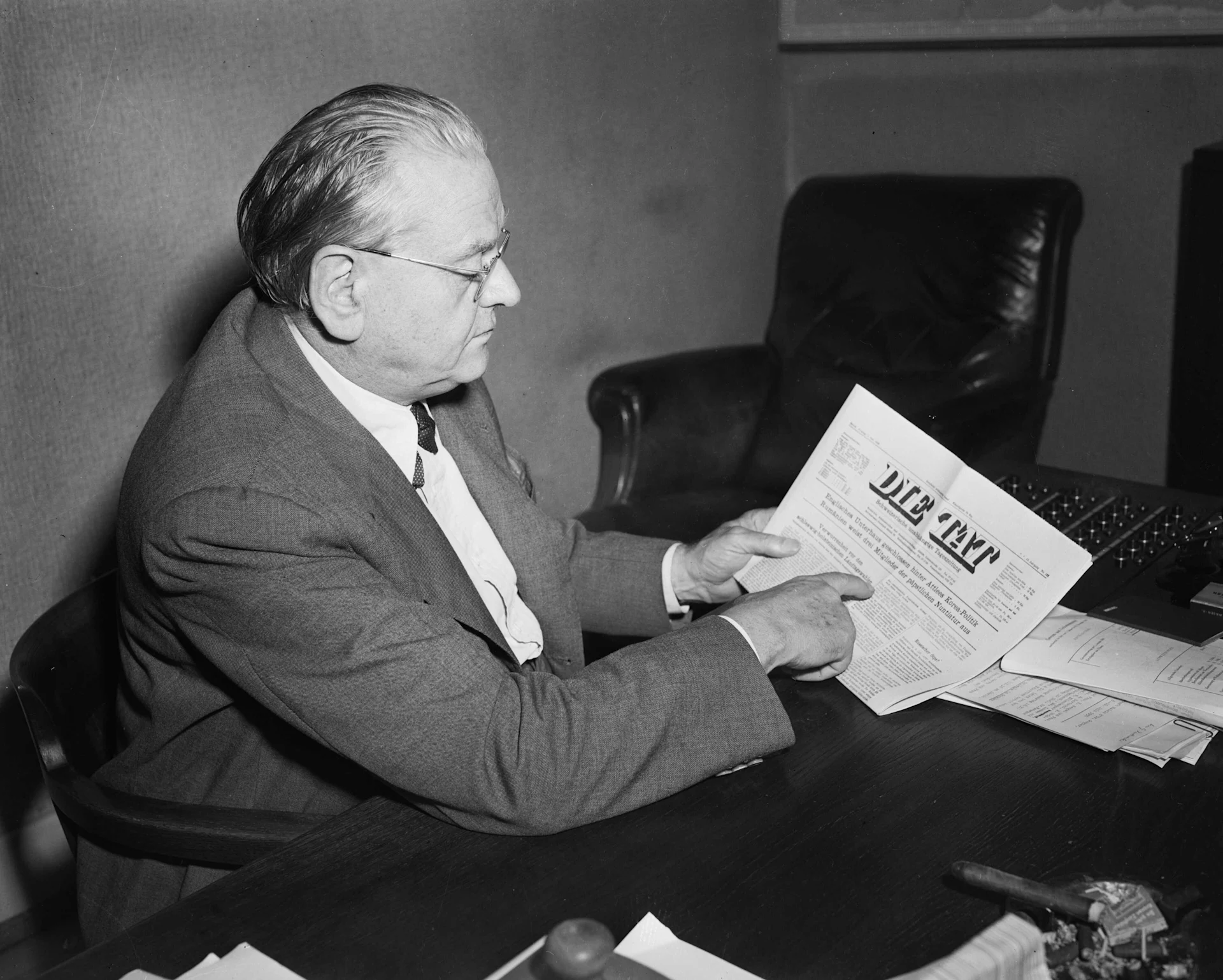

To fight the ban more effectively, Duttweiler entered politics, albeit reluctantly and to protect his own interests. He duly founded the Alliance of Independents party and was elected to the National Council in 1935. He remained a member of parliament for 24 years.

Due to his restless, impatient nature, Dutti repeatedly ruffled feathers on the sedate Bernese political scene. He was considered irascible and occasionally gruff and rude, but was said to have always been a good listener. He doggedly fought for commercial freedom and against cartels, often in court, even in the face of fierce adversity. He was repeatedly accused of lobbying for Migros out of pure self-interest.

Within the Swiss political world, he was seen as a tasteless and excessive businessman with unpredictable affectations.

In 1948, Duttweiler tried to table a bill demanding Switzerland stockpile essential goods in preparation for future wars. But because the National Council kept delaying the issue, Dutti's patience eventually ran out. In protest, he threw two stones at the Federal Palace, smashing a window in the process. His opponents saw this as proof that he had finally lost the plot.

In the 1910s, Duttweiler was still a regular food wholesaler who amassed a vast fortune that he lost again after the First World War. As head of Migros, he increasingly challenged conventional capitalism. He favoured a new market economy that would serve the people.

Ruthless Mancunian liberalism is dead. Long live responsible social liberalism!

Dutti matched his big words with equally big deeds. In 1948, he founded the Migros Club School, which made education affordable even for poorer people. In 1957, he established the Migros Culture Percentage. Through this organisation, Migros now spends CHF 121 million a year supporting causes for the common good. Dutti took his boldest step back in 1940, when he transformed his company into a cooperative. By doing so, he donated his life's work to the Swiss people.

Towards the end of Duttweiler's life, hostility towards him diminished and even the popular press began showing him respect. By then, it was generally agreed that he had done a lot for Switzerland and especially poorer people in the country

Because Duttweiler's marriage remained childless, he bestowed his paternal care on his 'Migros family'.

His death, in 1962, triggered an outpouring of grief. The funeral ceremony was held in Zurich's Fraumünster church, though even this wasn't large enough to hold the vast number of mourners who turned out. The ceremony was therefore broadcast to three other churches. Blick newspaper summed up the mood very succinctly at the time: "Dutti has simply left a huge gap in Switzerland.

A great philanthropist has died. The deceased may never have been a Federal Councillor, yet he turned Switzerland upside down in so many ways that it left many people deaf and blind.

How is Dutti seen today? 63 years after his death, he has lost none of his importance. He was an outstanding pioneer – a man who modernised life in Switzerland in many areas. Even those who don't know anything about him live in a country shaped by Dutti.

He was one of the century's greatest figures, a creator, an argumentative, fearless man. Gottlieb Duttweiler was the complete package: entrepreneur, publicist and politician.

The Migros founder was a visionary, lateral thinker and charming yet fiery character – and he did more than just reinvent shopping.

Discover exciting stories about all aspects of Migros, our commitment and the people behind it. We also provide practical advice for everyday life.