Migros anniversary

The year of celebration in orange

The many ways Migros celebrated its 100th birthday. A look back at Migros’ centenary.

navigation

Migros Group

What it takes to ensure that strawberry ice cream always tastes good, always looks the same and doesn't give you a tummy ache. Our editor found out.

“It isn't particularly cold here,” I think as I enter the Delica ice cream production factory in Meilen. With a hairnet on my head, I walk past booming filling and packaging machines. The iconic Migros strawberry ice cream featuring the monkey logo is one of the products made in the hall on the first floor. Today, it is being produced in a twin pack together with seal ice cream at a rate of about 24,000 ice lollies an hour.

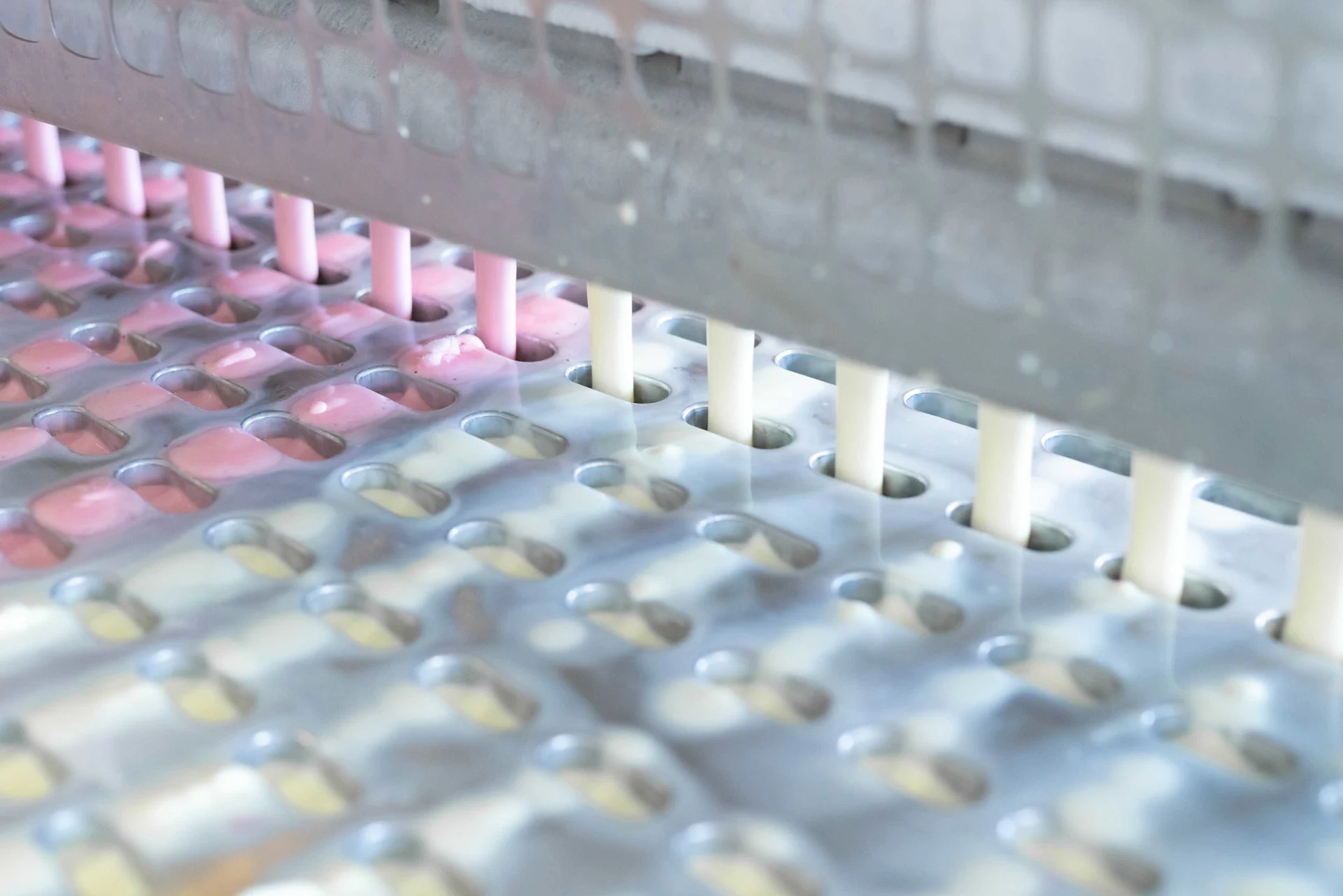

I meet shift supervisor Dominik Wechtitsch, who monitors quality in the production department. He takes me to the beginning of one line, where a turntable containing hollow moulds rotates. The creamy ice cream mixture is piped from the tanks to the moulds. During rotation, the mass cools and wooden sticks are inserted. “If the sticks are only slightly crooked, the machine can't grip the lollies,” Wechtitsch explains. Defective products are removed by hand.

His staff have even more to do if wooden sticks splinter. “Then we have to stop the system immediately and clean the entire turntable,” he says.

The ice cream produced on these lines can change from day to day – as can the mixture used. To prevent allergens and flavours being transferred from one product to another, the pipes are cleaned extensively after each changeover.

We take the lift to the ground floor. Dominik Wechtitsch wants to show me the room in which the ice cream blend is created, “Often one or two days in advance.” Just like everywhere else, we have to thoroughly wash and disinfect our hands before entering. An employee is pouring sugar into a kettle with an agitator: the blend for another day. The basic ingredients for strawberry ice cream are raw milk, cream, sugar, strawberry purée and chocolate.

A large, cylindrical, stainless-steel tank stands opposite the kettle. “In the pasteuriser, we heat the ice cream to 83°C for 25 seconds to kill pathogenic germs,” Wechtitsch explains. The machine is constantly monitored to control for even the slightest defect.

Wechtitsch points to an airlock leading to another area: the high-hygiene zone. “That's where we store the finished mixtures,” he says. Later on, they are pumped one floor higher through the pipes for further processing - without any human contact. The strictest cleanliness regulations of all apply in this zone. Only trained personnel are permitted inside. I must wait outside.

We leave the hygiene zone and reach the logistics area via a corridor. Up to 25 tonnes of raw milk are delivered here every day, as are 10 tonnes of cream. Delica obtains the strawberry puree and cocoa for the coating from Migros Industrie as semi-finished products.

Herolind Dinolli is responsible for receiving and storing goods. The logistics team leader and his three staff also prepare the finished ice creams for transportation. “Come with me. I'll show you where we get the goods from,” he says.

The lift takes us down another floor. As we enter the warehouse, the air is a frigid -28°C. Thousands of boxes of various sorts are stacked on shelves and pallets. “The ice creams have to be left to harden for a few hours,” Dinolli says. Fortunately, we don't have to spend long there.

There is a strict protocol for loading goods. Dinolli's team has just 30 minutes to take the ice cream from the warehouse to the outgoing goods area and pack it into a lorry. Before loading, they measure the temperature in the vehicle. Transportation only takes place at -18°C. “Maintaining the cold chain is our top priority,” he adds.

We head back to the factory on the first floor. Now, I'm standing on the other side of the ice cream production line, watching employees put pre-packaged ice lollies into boxes. If a package is defective, they remove the ice creams.

On the next conveyor belt, the boxes undergo two tests: a scale measures whether they are of the standard weight, while a metal detector checks for foreign objects. If they do not meet the target weight, the boxes are removed. And if metal is detected, they are separated. Flawless goods go straight to the deep-freeze warehouse.

Next to the ice cream line is a device that reminds me of a mobile cash machine. “That's our digital factory,” Dominik Wechtitsch says. It helps his staff with the regular spot checks. “There are precise specifications about how the ice lollies should look on the inside and outside.” Small bubbles in the chocolate coating are permitted, larger ones are not. All the specifications are reviewed using a checklist. Compliance is documented. This prevents faulty products reaching customers in the first place.

Staff by the conveyor belt check the flavour. This happens several times per shift, Wechtitsch assures us. Does the ice cream taste the same as ever? Is it nice and creamy? Does the coating crack when you bite into it? An employee trying a strawberry ice cream issues the verdict: “Perfect!”

My last stop is at the in-house laboratory on the second floor. Here, staff analyse everything from the raw materials to the finished ice cream. In addition to hygiene aspects, this also involves verifying other food standards, such as whether the ice cream mixture has the legally prescribed fat content, as deputy laboratory manager Nora Migliazza explains. “If not, we have to add cream during production.”

I notice a distinctly malty smell. “That's from the agar-agar in the Petri dishes.” The gel serves as a breeding ground for bacteria. If the sample is contaminated, dot-like microorganisms grow on it; an indication of pathogenic gut bacteria.

Raphaël Rossier has now joined us. He's the Head of Quality Assurance in Meilen. “If we detect any contamination, we narrow down the timeframe in which the problem must have occurred,” he says. This is possible because every stage of production is documented in minute detail. Thus enabling an affected batch to be identified quickly and removed. Further analyses would then follow. “However, contamination in production is extremely rare,” Rossier reassures me.

My head is reeling from all the information. Raphaël Rossier accompanies me outside. He hands me a strawberry ice cream to eat on the way home. Finally, I'm allowed to eat one.

Discover exciting stories about all aspects of Migros, our commitment and the people behind it. We also provide practical advice for everyday life.